Christiansen Family

About the Christiansen Family

Charles Christiansen was only 26 years old when he was killed in a logging accident while working for the Gualala Mill Company on Rock Pile Creek. Aside from his headstone inscription and a short obituary published in the local press, he died without leaving many records of his family origins or his brief life on the coast.

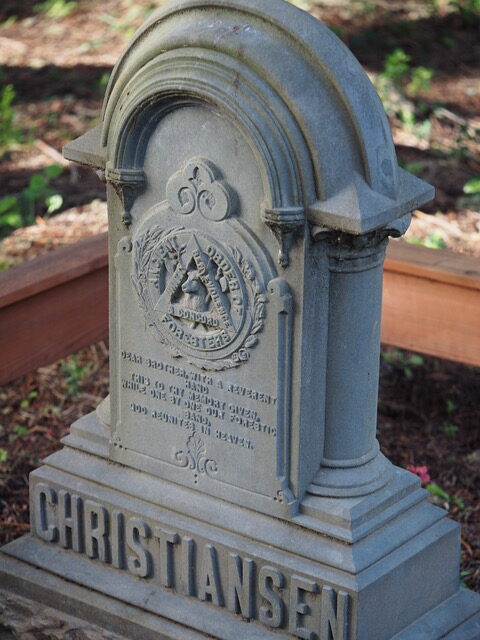

According to his headstone, he was born in Denmark on 27 April 1865 and died on 7 November 1891. He was a member of the Ancient Order of Foresters, a fraternal organization that supported its members with medical, health, unemployment, and burial benefits. A Mendocino Beacon news article (21 November 1891) describes the circumstances of his death, noting that Charles “was standing on a piece of timber and moving with a pole some other timbers, when the pole slipped and he fell into eight feet of water and was drowned in a few minutes.”

Charles was not listed in the 1880 US Census, indicating that he likely immigrated in the years following the census. Unfortunately, records in the 1890 US Census were lost to fire. Charles was unmarried at the time of his death, and he does not appear in any other local news stories.

The Beacon news article noted above states that Charles had two surviving brothers who lived on the coast. A records search revealed two men with the same surname in Mendocino County, James Christiansen and Hans Christiansen. However, further research on these men and their respective families failed to document a connection to either Charles or to one another.

The headstone marking the grave of Charles Christiansen was likely provided by the Ancient Order of Foresters. It is remarkable in both its unique design and exceptional state of preservation. The historic significance of this monument relates to its construction—a hollow metal casting of zinc, also known colloquially as “white bronze,” which was produced commercially by the Monumental Bronze Company of Bridgeport, Connecticut. Zinc monuments are known both for their intricate designs and imperviousness to the weathering that affects granite and marble. Zinc monuments were popular prior to 1914, when the company’s efforts were diverted to the production of ammunition during WWI. Following the war, demand fell off due to the increasing popularity of stone, and the prohibition of metal markers by some cemeteries. The Monumental Bronze Company did not survive the Great Depression and declared bankruptcy in 1939.

Research compiled by Jenny Hansen, AG and Kelly Richardson, APR, AG.